A Period of Extremes

(Wally earned his master’s degree from Purdue University and was a management consultant and operations manager at multinational corporations. While he has lived in both the US and Israel, he currently lives in Denver. Wally was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and has been interviewed on Israeli television several times about his journey with early-stage dementia. He is active in several organizations that focus on this condition and has agreed to share his journey in this blog. This installation is his first, but he also chronicles his experience in his blog TheLivingDyingDuet.com.)

===================

Knowing~Life Haiku

Knowing~Life Haiku

a haiku: knowing life through death

we can only know

our purpose in this life and

live life in a waythat is true to our

purpose when we fully face

our own death coming

Being 70 years old is for old people. Being diagnosed with early-stage dementia is for brain-falling-apart people. Needing help in living my life is for un-functioning people.

None of these had anything to do with me. None of them had anything to do with me until that day in October 2022 when the neurologist looked at the test results and told me that I have early-stage dementia. I thought that’s the worst news I would get, and it was, until January 2024 when the neurologist told me I also have Parkinson’s disease (PD).

PD has a bigger effect on my day-to-day life. I had figured out how to deal with forgetting so much because of the dementia, but with the PD, I physically couldn’t function as I had. I lost the practical use of my left hand in many ways — manual effort became a fingers-of-the-right-hand activity, and I didn’t dare pick things up since they would drop because of the shaking. Large physical limitations were added to the mental limitations, and the future looked very bleak from there.

What happened next couldn’t have happened without having first gone through these things. What happened was at first tiny and was completely overwhelmed by the terrible limitations that had come into my life, and it was just a feeling. It was a tiny feeling that oh-so-slowly started to take place in my life. And that’s exactly what it was — feeling.

As the brain-driven life I had lived up to then was reduced — as I went through mild cognitive impairment (MCI), to use the common phrase — there was room opened for something else besides the cognitive. That “something else” was feeling, and in a way I had never experienced before. The more I paid attention to it, the more it was there, and the more I felt happy that it was there.

I looked around and couldn’t find this described anywhere, so I made up a name for it, mild emotional enhancement (MEE), and created a web page describing it particularly as related to MCI. [That site is mciandmee.com.] And the flow continued. I kept hearing about mindfulness, and I felt something was missing there, too, so I created feelingfulness.com to go with it.

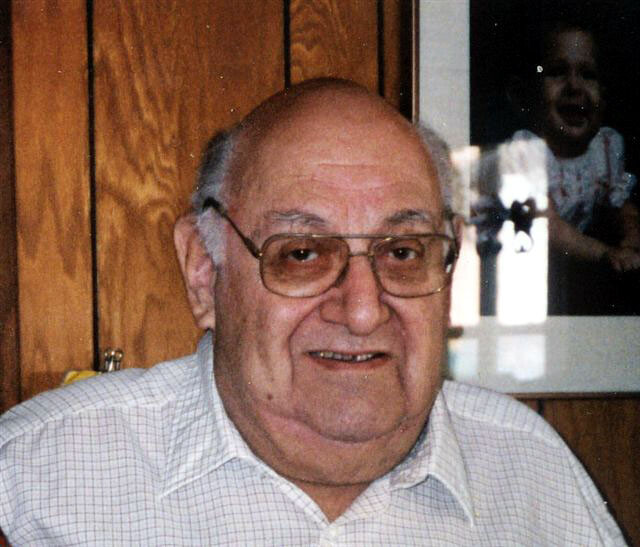

Let’s put words like these in our language and start feeling them and using them, and who knows where it will lead! I know where dementia leads, and as I’m on my way there, I want this approach to be available to me, so I invented I-Have-Now.com, which says that my life and my death are part of each other as the dementia advances. And for me expressing it, even on a T-shirt (see photo above), is part of feeling it.

I feel that a word that expresses what I’m going through is “release,” and that it’s important to me to explore this more. Actually, now that I realize that I’m on my way to the final exit, I feel that there is very much to explore here — I’ve been on the way since the moment I was born and didn’t realize it at all. We’re all here, and the world feels completely different when we realize that fact.

Let’s explore it together — I’ll tell you what I feel along the way on my journey, and I welcome your feelings as you are on yours.

Marc D Malamud

Transitioning Doula

The Quiet Gift of Sitting With Someone at the End of Life

the gift goes both ways.

Marc D Malamud

Transitioning Doula

The New Year's Resolution No One Talks About (But Should)

Make death contemplation part of your daily self‑care. Think of it as existential strength training. Start small. A few minutes. Here’s one easy Buddhist-inspired practice to try.

- Cuts through your bullshit. Excuses fall apart. What matters gets air.

- Clarifies your values. Priorities click into place.

- Boosts motivation. “Someday” becomes “now.”

- Deepens purpose. Meaning stops being something you chase and becomes something you make.

- Pulls you into the present. Life feels more vivid, right here.

- Amplifies gratitude. Even ordinary moments start to shimmer.

- Strengthens relationships. You forgive faster and love harder.

- Builds empathy. We’re all temporary; compassion gets easier.

- Ignites creativity. Mortality is powerful creative fuel.

- Keeps your ego in check. Humility = freedom.

- Encourages healthy risk-taking. Fear loses its grip; life opens.

The only thing scarier than dying is never having really lived.

Marc D Malamud

Transitioning Doula

What My Father Taught Me About Dying

Marc D Malamud

Transitioning Doula

“Why Wait Until the End? How to Confront Regret and Build a Legacy Now”

“Lessons from Deathbeds on Living Fully, Letting Go of Guilt, and Leaving an Impact”

The Nature of Regret

- Why didn’t I get help?

- Why didn’t I see the signs?

- Why did I make that choice?

- Why didn’t I know myself better?

Why Start Inner Work Now?

A Story That Says It All

What Legacy Will You Leave?

Your Turn

Marc D Malamud

Transitioning Doula

Subcategories

Obituaries & Memorials

This space is devoted to tender remembrance—a place to share stories, blessings, and the everyday moments that made each life uniquely precious. Through these tributes, we honor each beloved soul’s transition, hold their spirit close, and gently accompany the hearts who continue on without them.